The Double Choreography: Inner and outer dance

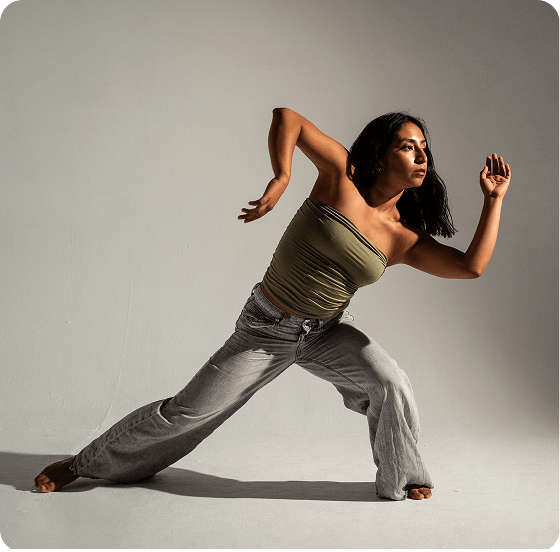

Throughout my years as a dancer, I have become increasingly aware of the double choreography that every dancer lives. There is the choreography we show to the world — the one made of form, rhythm, and space — and then there is the invisible one, unfolding quietly within.

The outer dance is a conversation of steps, spacing and tempo; the inner one is a dialogue of thoughts, emotion and focus. The two are inseparable. When the inner dance falls out of rhythm, even the most polished movement can lose its truth.

Timothy Gallwey, in The Inner Game of Tennis, spoke of the player’s greatest challenge not being the opponent across the net, but the one inside the mind. In dance, the same holds true. The real mastery begins when we learn to let the mind and the body move together — not in conflict, but in conversation.

When this relationship becomes harmonious, effort softens into flow, self doubt fades into awareness, and movement becomes not just an act of performance, but an act of presence.

Dancing with the Monstruitos: when the Mind loses Flow

Every dancer has met them — the small saboteurs of the mind, the voices that turn focus into fear and play into pressure. I call them los monstruitos, the inner voices of doubt and expectation that creep in just when we need clarity most. They whisper comparisons, amplify fears and make us forget the simple joy of moving.

The body may want to move freely, but the mind demands control. The muscles tighten, breath shortens, and expression turns mechanical. This inner tension isn’t a flaw, but a reminder of how closely our artistry depends on psychology.

The goal of the “inner game” is not to silence those monstruitos, but to retrain them so they can be transformed from saboteurs into signals, from critics into curious partners.

The Mind as a Partner: Awareness Over Control

Awareness begins where ordinary listening ends. We spend years listening to the rhythm outside of us, yet awareness teaches us to listen within.

Moshe Feldenkrais wrote,

In other words, becoming aware of our habitual patterns is the first step toward having the freedom to move differently. In this sense, awareness is not abstract but physical: the foundation of intelligent movement and the bridge between mind and body.

Instead of thinking “I must not fall”, the dancer Learns to think “I am feeling unstable; let’s rebalance”. Instead of “Everyone’s watching”, it becomes “I’m sharing this moment”.

Awareness transforms control into flow. It invites the mind and the body to move together, in mutual understanding.

Yet even with this understanding, there are moments when the dialogue falters, when the mind slips back into old habits of control, comparison or fear. These moments don’t mean we’ve failed; they’re simply part of the dance between growth and resistance. Learning to recognize them is where the inner work truly begins.

Common Battles in the Inner Game

Performance Anxiety

I’ve seen dancers take the stage with their hearts racing and breath caught halfway to the lungs, as if their bodies were running ahead while their minds tried to catch up. That adrenaline isn’t failure; it’s energy asking for direction. Breathing and visualization can help transform that rush into focus, turning fear into presence.

Perfectionism & Self-Criticism

Many dancers carry a constant whisper of “not enough”. I’ve watched students push through exhaustion, chasing a version of perfection that keeps moving further away. When we shift from “I must be flawless” to “I want to express fully”, something softens. The movement regains sincerity and the dancer’s humanity returns to the room.

Body Image & Self-Perception

It’s impossible to spend years in front of a mirror without developing a complex relationship with one’s reflection. Early in my ballet training, we didn’t have mirrors for a couple of years after I arrived — they simply hadn’t been installed yet in my hometown studio. Looking back I realize how much that period shaped my sense of proprioception, body awareness, and trust. I had to rely on my teacher’s external eye (luckily, she was wonderful!) And, more importantly, my inner one.

That early experience became the seed for how I teach today. In many of my classes, I cover the mirrors with curtains. It helps dancers shift attention from how they look to how they feel — from a 2D reflection to a 3D experience of moving through space. The mirror can be a useful tool, but it can also become a wall between body and presence. When dancers stop measuring themselves against that surface, something remarkable happens: movement becomes authentic again.

I like thinking that our bodies are not objects to be judged, but living instruments of expression. The moment a dancer begins to move from sensation rather than evaluation, the dance changes — it breathes again, shifting from perfectionism toward process, from outcome toward experience.

Motivation and Burnout

In a world built on comparison and achievement, it’s easy to forget why we began dancing. I’ve met dancers who felt empty even after receiving recognition because they were moving for approval. Reconnecting with intrinsic motivation — the joy of moving, exploring, creating — restores lightness to the work. It’s not about doing less, but dancing from a different place inside.

Injury and identity

An injury can feel like being exiled from one’s own body. I have myself struggled with stillness, afraid I’ll lose my identity if I can’t dance. Yet I’ve also witnessed how often dancers return from injury with new depth and understanding — more patient, more attuned. Healing is slow, but it teaches presence in a way that no technique class ever could.

Inner Practices for Outer Flow

Psychological skills can be practiced just like pliés or turns. They are part of a dancer’s technique — invisible to the eye but essential to the art. In the same way we strengthen muscles, we can train the mind to support rather than sabotage our movement.

I often remind my students that mental training is not a luxury; it’s part of professional preparation. Breathing, grounding, visualization, and reflection are as vital as stretching or balance work. Over time, these practices help us rely a little less on external reassurance, as we begin to discover steadier sources of confidence within ourselves.

Here a few small but powerful practices that nurture the mind-body partnership:

The Centering Breath (4-7-8)

Before performing, I sometimes take one minute to breathe consciously, especially when I am nervous; inhale for four counts, hold for seven, exhale for eight. I like this exercise because it’s simple yet surprisingly effective. The breath slows the racing mind and brings awareness back to the body. At that moment of calm, clarity can return.

Grounding the senses

When anxiety pulls attention away, use the five senses to come back. Notice what you can see, hear, touch, smell and feel. This sensory check-in anchors presence — it reminds the body that is here, now, safe to perform.

Compassion Check-in

Our inner dialogue can be harsher than any teacher’s correction. When you notice yourself being self-critical, try pausing and asking, “Would I speak to a friend this way”?. That simple question can transform criticism into care. The goal is not indulgence, but respect for the human being behind the dancer.

Visualization

Before a class, rehearsal, or performance, close your eyes and mentally walk though what’s ahead. Imagine moving with ease, strength and joy. The brain doesn’t distinguish much between imagined and physical practice, so this rehearsal strengthens both confidence and neural patterns.

Reflective Journaling

After dancing, take five minutes to write — not about what went right or wrong, but what you noticed. Reflection integrates learning and helps spot emotional patterns. What inspired me today? When did I feel free? What tightened me? Journaling shifts the focus from judgment to understanding.

With time these inner practices start to weave themselves into movement. Breath, focus, compassion — they stop being separate exercises and become part of how we dance, rehearse, and live. The goal is no longer to control the mind, but to include it. When awareness becomes second nature, freedom can return — not as something we chase, but as something that quietly unfolds from within.

Winning the Inner Game

There comes a moment in every dancer’s path when effort gives way to ease. Technique is still there, discipline still anchors the body, but movement begins to arise from a quieter place — one of trust, presence, and connection. This is what I call inner freedom: when the body remembers and the mind allows.

True artistry doesn’t mean losing control; it means no longer needing to hold on so tightly. The mind and body start to cooperate rather than compete, and expression becomes inevitable, as natural as breathing.

Inner freedom isn’t a permanent state but a living rhythm. It appears when we listen, when we let movement speak before thought interrupts. It’s felt in those fleeting moments when time softens and awareness widens, when dancing feels less like doing and more like being.

This is the heart of the inner game: learning not only the choreography of the body but the choreography of attention. The more we attune to that dialogue, the more unfiltered our dancing becomes.

By Martha Graham

To dance with awareness is to let both body and mind be seen, not as separate performers but as partners in the same unfolding phase. When we meet ourselves in that space —awake, imperfect, alive — movement becomes expression and expression becomes art.

At the end, the real victory in dancing the inner game is less about winning and more about remembering who we are when we move without fear — when mind and body meet in honest motion.