“Whoever you are - I have always depended on the kindness of strangers”

Blanche’s final speech, possibly Tennessee Williams most famous line in his greatest play A Streetcar Named Desire, epitomises the queerness, the otherness, that pervades his work.

About Tennessee Williams

Thomas Lanier Williams. (1911 -1983) was born in Columbus Mississippi and raised in St Louis Missouri. His family, who were very influential on his writing, included his father, Cornelius, an alcoholic travelling shoe salesman, who despised the young Thomas’s effeminacy. He was very close to his mother Edwina and elder sister Rose whose neurodiversity later led to a lobotomy. He had a younger brother and was also close to his grandparents. All these relations had a major influence on his plays

Tennessee Williams plays

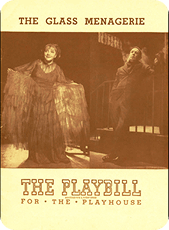

Williams attended the University of Missouri where he started his writing. He had little initial success leading to depression and a nervous breakdown, until 1944 when The Glass Menagerie, premiered in Chicago and transferred to Broadway where it won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award in 1945.

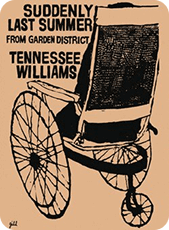

He went on to write many extremely successful plays including A Street Car Named Desire (1947) Cat On A Hot Tin Roof (1955) and Suddenly Last Summer (1957), all of which were made into films and he is often ranked with Arthur Miller and Eugene O’Neill as one of the United States most successful twentieth century playwrights, as well as being the pre-eminent queer playwright of that century.

Tennessee Williams as a gay author

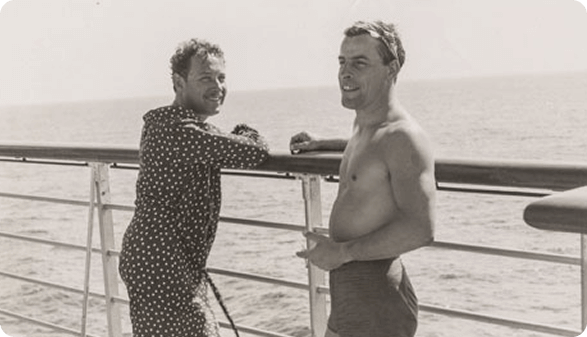

From the late nineteen thirties Williams had a number of relationships with men. His happiest and most enduring relationship was with Frank Merlo which began in 1948 and lasted until 1963 when Merlo died of lung cancer. For most of his life he was openly queer, nevertheless he grew up at a time when sodomy was illegal in the U.S. and the very subject of homosexuality was not to be mentioned and this obviously affected his writing.

The representation of homosexuality in American theatre was outlawed until the end of the 1950s on the grounds that it would lead to the corruption of youth and encourage homosexuals to become visible. While Williams did not write directly about queer issues or have overtly queer characters in his major plays there was a queer subtext to all his work which we shall look at.

Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie

The Glass Menagerie is so heavily influenced by Williams family that it is almost autobiographical. The narrator and participant in the drama, which revolves around a mother and daughter’s desire for a “gentleman caller”, is even named Tom after its writer and the mother and daughter are both based on his own relations. The simple plot which climaxes in the gentleman caller’s revelation that he is about to be married is surrounded by the depiction of complex family relations portrayed with great poetical beauty.

Most interestingly from our perspective the enigmatic character of Tom Wingfield is very much an outsider who is constantly escaping the house to go to bars and the movies. His mother tells him accusingly:

“You live in a dream, you manufacture illusions!”

Many commentators have suggested that he is going out to have queer relationships and many productions have also implied this.

The “dead gay guy” features in several plays. The “dead gay guy” features in several plays.

Blanche DuBois in Streetcar Named Desire

In Streetcar Named Desire the central character of Blanche DuBois is visiting her sister Stella, who is pregnant, in New Orleans after a succession of disasters in the family home including discovering that the man that she married, now dead, was gay. She spars with her sister’s husband Stanley who on the night Stella gives birth rapes her. Not only did Blanche have a queer husband but there is something about her character, her behaviour and the way she is written that has led some writers to suggest that Blanche herself might be queer. Famously she covers up the light bulb in the living room with a paper lantern:

“I can't stand a naked light bulb, any more than I can a rude remark or a vulgar action.”

Her delicate beauty must be protected. Her past must be concealed. Blanche is a broken person who has a painful past and is in a desperate and continual search for love and protection, which some have found to be queer. Certainly around the “steamy” plot Streetcar clearly deals with questions of gender both heterosexual and queer.

Brick in A Cat On A Hot Tin Roof

Maggie the cat in A Cat On A Hot Tin Roof is struggling to hold on to Brick her husband who refuses to have sex with her and is in mourning for his best friend Skipper, who he believes Maggie has slept with, and that she:

“Poured in his mind the dirty, false idea that what we were, him and me was a frustrated case of that ole pair of sisters that lied in this room, Jack Straw and Peter Ochello. - He poor Skipper went to bed with Maggie to prove it wasn’t true, and when he didn’t work out he thought it was true! - Skipper broke in two like a rotten stick- nobody ever turned so fast to a lush - or died of it so quick……”

This very explicit passage about homosexuality and its implication, here and elsewhere, that there was a queer bond between Brick and Skipper was omitted from the film.

While on the surface this might seem to be Williams expressing disgust at his own sexuality, given the time it was written a more sensitive reading might see it as the author portraying the struggle of homosexuals in a world where queer desire was “the love that dare not speak its name”.

Another major theme of the play is “mendacity”. “Mendacity is a system that we live in,” declares Brick. “Liquor is one way out an’death’s the other.” Again there are queer implications here.

Sebastian Venable in Suddenly Last Summer

The third “dead gay guy” is Sebastian Venable in Suddenly Last Summer. Sebastian’s mother is desperate to discredit the account of his death being relayed by her niece Catherine, to the extent of attempting to get her lobotomized.

Sebastian (who we never see) is clearly portrayed as gay. He is a “celibate” poet and the apple of his mother’s eye. But Catherine has been lured into importuning for him on the beach at Cabeza de Lobo. The crowd of young men and boys that are attracted eventually pursue him and Catherine claims they rip him to pieces and devour parts of his body. This horrific story, the telling of which this one act play builds to, ends with the doctor saying that maybe the story could be true.

In the film we see Sebastian’s figure but never see his face and as this was a Hollywood suspense thriller of its time, we are not permitted to glimpse his homosexuality either.

Tennessee Williams himself, while cooperating on the films of his work voiced his own displeasure at their censorship and sanitization.

Challenging the censorship of the times

We can see that queer characters are present in William’s major plays and indeed why would they not be? All writers write from their own experiences but queer writers in the past, and in many countries today, self censor or sublimate the queerness in what they write in order to make it more acceptable or even legal. This was not just true of Williams but of many other great American queer writers including Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman.

Nevertheless great queer writers have often, consciously or unconsciously, found ways to embody queerness in their texts even if that queerness is ignored or minimised by the guardians of the prevailing culture. Melville’s Billy Budd Sailor for example is shot though with homo-eroticism without anything being explicit. And it is held up in US as a novella about jurisprudence and the queerness is completely ignored. So too the queer undercurrents in Williams great plays whose scandalous and steamy nature has been concentrated on at the expense of its subtle descriptions of the “other”.

In more recent times with the advents of queer studies and queer theory and a general acceptance in the more progressive echelons of society that gender and sexuality are fundamental to our understanding of any work, many writers have looked at the ways in which queerness, other than in the, mainly offstage, characters is portrayed.

Some writers have seen Williams plays as challenging the dominant narrative of heteronormativity and giving voice to marginalised experiences. Others have suggested that the theatrical style of his plays with their emphasis on emotion, excess and often exaggerated characters and indeed the poetical nature of the language itself lend themselves to queer interpretation. Williams characters often challenge gender roles and embrace the fluidity of sexuality. Individuals hiding their true identities (the closet) is a recurring theme in his work.

Public acknowledgement

Williams himself was openly gay and publicly acknowledged his homosexuality after the Stonewall riots. His gay identity and its influence on his work has been much written about, sometimes concentrating on a perceived self loathing or wrestling with homophobia but in more recent times exploring the complexity of his relationship with his identity.

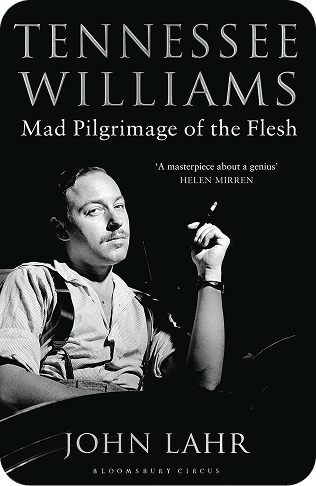

What is clear is that these magnificent plays have more than a little queer subtext as befits one of our greatest queer writers. They are widely available in bookshops, online and assessed in detail in a splendid biography by John Lahr appropriately titled: Tennessee Williams Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (Bloomsbury Circus 2014)

Suggested resource

Tennessee Williams Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

By John Lahr (Bloomsbury Circus 2014)