Who are your creative heroes?

Who are your creative heroes? After forty years of acting, directing and swimming about in the great ocean of stories, perhaps it’s not surprising mine are writers, especially those who write for actors. I’m in awe of their relentless courage in adventuring to mysterious worlds, descending like free divers to dangerous depths, returning with weird tales and bizarre characters. Ask me whose plays have affected me most deeply, or whose I most enjoy directing, and I’ll answer with one name: the late British dramatist Harold Pinter.

I was fifteen when I saw my first Pinter play. Most of it went right over my head. But I’ve never forgotten the amazing atmosphere, the intense tension, the dreamlike blend of humour and weirdness. A few years later, just as I was starting drama school, by pure chance I met him, clueless that this was the beginning of the most important friendship of my life.

Fighting fascists

Pinter’s impact on actors, writers, directors and audiences over the last fifty years or so is impossible to ignore.

In following his own distinctive drumbeat he led drama away from conventional realism and naturalism in a new and disturbing direction.

He was at the very top of his profession for fifty years, winning Baftas, Tonys and Oliviers. He never thought of himself as a leader. But because of his authority, uncompromising style and fearlessly humanistic vision, many people myself included looked to him for leadership and inspiration.

Pinter was a good man to have at your side. As a youth once or twice he and his mates fought fascist thugs on the streets of East London. His reputation for anger was fearsome, and it’s true if you rubbed him up the wrong way he could be terrifying. But once he trusted you he was very generous, always encouraging and loyal to a fault. He gave me so much, and I miss him every day.

I was truly lucky to get to know him well. They say the best way to keep the gold you’ve been given is to find ways to share it. So that’s what I try to do. But even Pinter would agree that, for an inexperienced young actor meeting him for the first time, it doesn’t hurt to have a simple key to unlock the door that leads down into the dark world of Pinterland.

Hopefully this piece offers such a key. A few bits of biographical background will oil the wheels.

Artist profile highlight

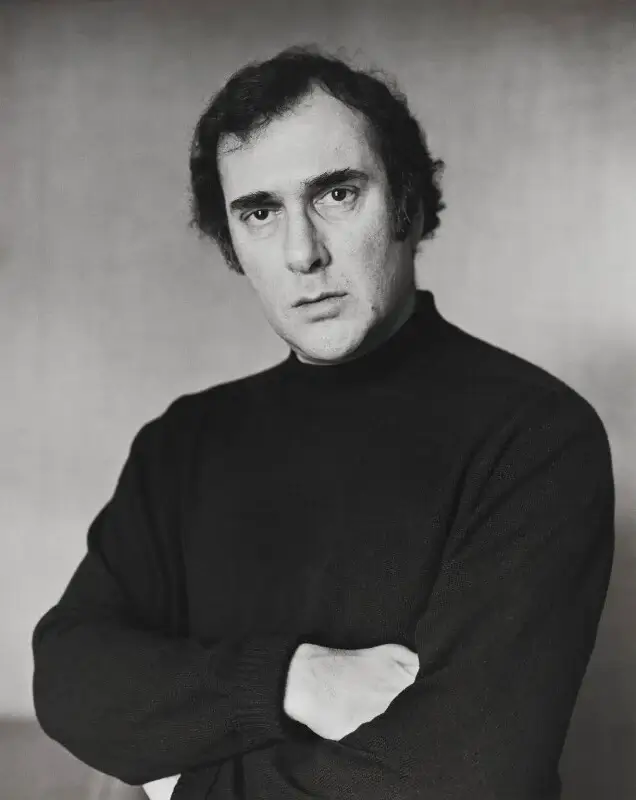

Harold Pinter

1930 – 2008 · 🇬🇧 British

Harold Pinter was one of the most influential British playwright, screenwriter known for his sharp, tense dialogue and exploration of power and ambiguity.

Occupation

Playwright, screenwriter, poet, director and actor

Notable accolades

Nobel price in Literature

Laurence Olivier Award

David Cohen Prize

Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour

Sex and death

Born in 1930, Pinter was an only child. His father worked in a tailor’s shop. Family life was warm and loving, but they didn’t have much. There were very few books in the house. His writing life began around the age of eleven, starting with poems. Pinter’s appetite for literature begins and ends with poetry. Along with the game of cricket, words were his first passion (girls came a bit later). He was electrified by the fizzing current that was generated when certain sounds and clashing words were crunched together. The resulting rhythms were irresistible to the young poet’s ear.

Still a boy at the outbreak of World War II, Pinter watched one night as the lilac tree in his garden was set ablaze by a firebomb. A few years later during a raid he had his first erotic encounter in an air raid shelter with a girl who lived up the road. The imminent danger of death, coupled with the excitement of awakening sexuality even as fire and destruction rained down from above had a visceral impact on the imagination of a lad already throbbing with an irresistible impulse to write poetry.

Jewish

Born a Jew, the teenaged Pinter found his true voice as a writer even as the massacre of millions of fellow Jews in Europe became public knowledge. He was in no doubt as to the fate that would have befallen his family and closest friends had Hitler’s stormtroopers crossed the English Channel. At the same time he was busy at the public library devouring with precocious zeal the fiction of Dostoevsky, Henry Miller, Hemingway and Steinbeck, along with the understated cool of Miles Davis, and Bach’s, sublimely essential music. He even joined a film club and discovered French and Russian cinema, American gangster movies, and the surrealism of Salvador Dali and Luis Bunũel.

In 1947, faced with the choice of serving two years’ National Service in the army, navy or air force, Pinter refused outright, declaring himself a Conscientious Objector. Despite his parents’ agonised protests Pinter stood his ground. He was twice tried by a military Tribunal. He took his toothbrush with him to court, certain he would be sent to prison.

Somehow he escaped with a fine. Perhaps the Tribunal’s judgement was tempered by Pinter’s impassioned statement:

“To join an organisation whose main purpose is mass murder, whose conception of true human values is absolutely nil, and whose ambition is to destroy the world’s very, very precious life, is completely beyond my human understanding and moral conception… To take one human life is completely alien to my moral code.”

Silence

He tried drama school a couple of times but Pinter was happier learning on the job in the real world. By the age of twenty-one he was already a working actor. Over the next few years he appeared in numerous productions of Shakespeare, and many other somewhat mediocre plays.

From these experiences he swiftly learned the basics of stagecraft, audibility and physical control. “I learned from acting what would shut an audience up,” he said later about writing plays.

When a playwright succeeds in shutting the audience up, the silence can be very powerful.

Indeed Pinter’s use of scripted silences has had a huge influence on subsequent generations.

But Pinter himself cannot be silenced. Since his death in 2008 the twenty movies he scripted have been recognised as classics, while his twenty-nine plays continue to be produced all over the world. Let’s explore why.

Just so

A Pinter play is a “just so” story: things are just the way they are.

We’re familiar with this quality of stories from fairy tales and folklore – not to mention our nightly dreams with their crazy images and wild storylines.

In “just so” stories the characters do what they do, say what they say.

On the surface things are often outlandish, frequently ambiguous, and sometimes downright confusing. That’s the point about just-so stories: though rich in vivid images and possible meanings, they can never be explained. We are bound to try to figure it out for ourselves.

Some playwrights are delighted to sit in the rehearsal room with a pad and pencil ready to add a few lines, or even compose a new scene. Not Pinter. With Pinter the text is the text. Once he had completed his editing process (he admitted to sometimes cutting too much) it was almost unheard of for anything more to change.

The reason the precise form of the finished script is of the utmost importance to him is because he is a poet. We could argue that he was a tyrant to insist on such a degree of control. But poets are poets for good reason. What obsesses them – aside from working and re-working the precise form of a poem to discover the essential language to express a mystery – is economy of means. Pinter stated his poetic philosophy very clearly in a line from his only novel, The Dwarfs, written in his early twenties, several years before his first play:

“Every particle of a work of art should crack a nut, or help form a pressure that’ll crack the final nut.”

Nutcracker

Rehearsing a Pinter play is best when we are accompanied by an actor-friendly director who can help us become receptive to Pinter’s wavelength, a frequency shaped by growing into adulthood through wartime terror, an era of genocidal racism, and a magnetic pull towards erotic obsession.

And also a love of poetry. What are poets interested in above all else? They want to use language and rhythm to shift our sense of time into the dimension of eternity; to enter the deep mystery of what it means to be a human being, inhabiting the wild space between womb and tomb where we’re compelled to experience extremes of bliss and agony. Why? Because life is short and freedom is priceless.

Pinter’s writing life may have started from an impulse to express an authentic sense of being alive in a momentous time, mythologising his personal experience.

But in 1956 Pinter the poet expanded into Pinter the dramatist with his first play THE ROOM. Written in two days, the play expresses his sense of life’s ridiculousness and brutal absurdity, a comic thriller dancing on a razor’s edge between heightened realism and the surreal edges of sanity. For characters trapped in these threshold spaces hyper-vigilance is the order of the day.

For the actors every easy assumption must be challenged. Nothing and no one can be trusted at face value.

Harold Pinter plays highlights

Something Is Happening

Early rehearsals of a Pinter project may leave us feeling delighted, frustrated or both.

Search as we might, we don’t seem to have been given all the necessary information. We could be forgiven for feeling that someone has deliberately withheld a good deal of vital background information:

- Characters enter and exit without adequate introduction.

- Things take place that seem to defy logic.

- People act unpredictably without offering any reliable account of themselves.

- The separation of the past and the present seems at best uncertain, at worst downright confusing.

- Darkness suddenly overwhelms the stage.

- Violence explodes out of unbearable tension.

- It’s impossible to be certain that anyone is speaking truth.

There’s a tremendous tension in the play’s atmosphere, yet we can’t readily identify its source.

Reading the script aloud we laugh spontaneously, then cover our mouths with horror. What kind of people laugh at cruelty and mockery? What does it mean? How on earth are we supposed to act in a play where no one can explain for certain what the hell is happening?

But something is happening. We sense it, however frustrated we may be by not being able to articulate it at first. One of Pinter’s plays even begins with the opening line: “Something is happening.” The question we are obliged to ask is: what?

Stranger Things

It helps to discover that the often confused, sometimes deranged people we meet in a Pinter play reflect life as he experienced it. Frequently he attracted random people who approached him uninvited to tell him their bizarre stories. And we know from our own lives that sometimes – at funerals, in the supermarket, at the busstop – people we’ve never met or seen before decide that we are the person with whom they need to share the lunatic stuff they get up to, or fantasise about doing, or feel haunted by, or guilty and ashamed of.

Naturally we’re disturbed by such people. And yet, if we’re honest, aren’t we all just mirrors of one another? It’s actually very human indeed to be strange. What’s truly strange is how we’re convinced we hide our weirdness from others.

Pinter didn’t faithfully write down every word of such encounters, but he was a wonderful listener. His imagination had a sort of photographic facility. If the image of something he saw or heard really stuck with him he could re-enter and explore it interactively. Sometimes such an image would offer itself as a conduit down into the depths of his imagination where, on a good day, more might be revealed. He intuitively felt that these images. and the snatches of dialogue which sometimes accompanied them, were clues to a compelling mystery. His job as he saw it was not to solve the mystery, but to track the clues as close as possible to their origins to see if he could tune in to what followed.

When the technique worked, he was able to get down what he heard on paper, even see in imagination the people who were speaking. All this would happen in an overwhelming volcanic surge of creative energy.

The Meaning Behind The Meaning

Pinter might have won a Bafta and the Nobel Prize, but ultimately he’s a flawed human being telling it as he sees it. So when encountering a Pinter play it’s a good idea to let go of any excess reverence. But the non-negotiable fact remains: we can’t change Pinter’s script. It’s down there in black and white and sooner or later we’re going to have to surrender to it. This can generate a certain amount of aggravation. Resistance to surrender is a perfectly natural response to ambiguity after all, and not all actors are comfortable swimming around in a sea of ambiguity. We prefer to find out quickly what we’re meant to be thinking and then lock it down, trying too effortfully to figure Pinter out when what’s needed is patience. It’s all too easy to charge forward and miss a vital clue before we’ve locked onto his wavelength. We need to learn that’s what’s not spoken is often as potent as what is.

Back in 1963 Pinter’s assistant director kept a rehearsal diary and jotted down the playwright’s advice to his actors at a point when they were feeling bogged down in their attempts to define the precise meaning of every line:

“It isn’t a question of: ‘It doesn’t mean this, it means that.’ If you hit a line with particular emphasis within the rhythm the line will become clear. A half-hour debate can be far more confusing and obscure than one clearly put sentence. Music and rhythm, they must be your guides…so don’t let us get bogged down in abstract discussion.”

Trust The Text

In other words we must have faith in Pinter’s text, and trust that he’s not interested in bewildering the actor or the audience merely for the sake of it. The nature of what is happening both above and below the surface of the action is usually revealed to us incrementally via patient exploration rather than full frontal assault. Trial and error is the very nature of rehearsal. The team that walks this road of discovery together finds itself in a creative process which yields thrilling results over time, not instantly but gradually. The key is to trust the text. It’s not completely blind trust: we must question everything, of course, and, like Pinter’s characters, find ways to endure the discomfort of not being certain of where we’re going.

Acting requires guts, patience and resilience. It can be a very lonely activity. I had the good fortune to work a few times with Pinter. Part of his generosity actors was that, rather than playing God, he was just as genuinely intrigued and perplexed by a line as the actor

tasked with finding the best way to say it. Pinter would support his cast in every possible

way, and from time to time actors would ask him directly for the meaning of an ambiguous

line. Pinter would smile and purr: “I’m afraid the author has no further information.”

Everybody laughed, but the point was that preferred the actor to persist with patient

exploration than himself be cornered into making a definitive statement about something

ultimately indefinable. The actor knew there was still some groping about in the dark

ahead, but that the author was at his side throughout.

Breaking down Harold Pinter's The Room

A View Of The Room

Let’s use THE ROOM to look in a little more detail at the challenges facing us in rehearsal. The room in question is a bleak upstairs bedsit in a large house. Its occupant is a woman of forty or so called Rose. Rose is the play’s pivotal character. She potters about wittering compulsively, fetching and carrying, soothing herself with the sound of her own voice as she serves her silent husband egg and bacon, pours his tea, butters his bread. She speaks with anxious curiosity about sensing a stranger living in the damp, dark basement. She pivots back and forth between anxiety and reassurance. Again and again she returns to how lucky they are to have their room, a place where you can keep yourself to yourself and be left untroubled by the world, invisible. Bert, her husband, utters not a single word. The more Rose talks about how their room is the very source of her threadbare sense of well-being, the more the audience begins to sense the trouble that’s coming for Rose.

Given Circumstances

We talk in rehearsal about a character’s ‘given circumstances’. What can we say in Rose’s case? It is teatime on a winter’s afternoon. The weather outside is arctic. She’s poor – despite the freeze the gas fire is unlit. She mutters about the cold, the wind, the snow that’s forecast to fall, the icy roads that Bert her husband is determined to go for a drive on. Rose mentions they’ve both been unwell for a few days. She has cooked a meal for Bert. She’s obsessed with the identity of the stranger in the basement.

The script tells us her name is Rose. But no one calls her that. Actually by the end of the play she’s answering to ‘Sal’, the name she is called by a blind black man called Riley who has been in the basement all weekend waiting to deliver the message that her father wants her to come home. When Riley first entered her room Rose swore she didn’t know him and abused him. Now the word ‘home’ from his lips devastates her. Earlier she said the room was all the home she needed. But from Riley we learn Rose has another home. And a father.

Five minutes after unleashing her terrifying racism she is holding Riley’s hand, tenderly stroking his face with an almost childlike love and affection. What is the source of the warmth of which now floods her? At first she resists him calling her by the name Sal. But each time Riley softly repeats it her resistance melts. “Now I see you,” the blind man says without irony. “Now I touch you.” Before our eyes Riley’s touch seems to be healing her. Too late.

Often in these early pinter plays the main character has left it too late to influence their circumstances for the better. The consequences of their procrastination – however understandable – tends to be devastating. The actors might not be absolutely certain of every last fact, but there’s no mistaking the fate that awaits someone who has made bad choices in their desperate need to is hide from the past. The actors in rehearsing plays who can flow with the unfolding mystery will fare best in performance. Others will feel frustrated, sensing that information is being withheld. Either way, none of the startling climaxes in these plays is so thoroughly explained that the audience can understand rationally what is happening. Instead, they feel it emotionally – a more powerful form of knowing – through the poetic quality in the writing, including what’s not spoken.

Our questions are legitimate: what happened to Rose that she left ‘home’ and her father? Who is Riley? If she knows him, in what context? And why does she go to such extremes in denying him when he first enters the room? What is Riley’s connection to her father? Why does he call her Sal? Is that her name? If Sal is her name why is she calling herself Rose? In what circumstances do people live under two very different names? If for some reason she has felt compelled to get away from her father and ‘home’, how long has she known Bert? What is the nature of their relationship?

Remember I said Pinter is a just-so playwright!? But these are the questions the actress playing Rose is honour-bound to ask, even while knowing that absolute certainty may never be forthcoming. Our faith is that as the work progresses frustration gives way to a greater sense of curiosity, bafflement yields to compassion as Rose’s profound loneliness grips the entrails of the actress playing her. Understanding flows where earlier we felt almost overwhelmed by self-doubt. Perhaps the self-doubt never leaves entirely, but alongside it a flow of courage and commitment comes on stream, supporting our continuous exploration. The joy of working with Pinter is that more is constantly being revealed, in response to our patient investigation of the humanity of these much-conflicted characters.

The Last Word

Let’s give the last word to Harold:

“The world is full of surprises. A door can open at any moment and someone can walk in. We’d love to know who it is, we’d love to know exactly what he has on his mind and why he comes in, but how often do we know what someone has on his mind, or who this somebody is, and what goes to make him and make him what he is, and what his relationship is to others?”

© Harry Burton 2024 Harry’s Channel 4 documentary Working With Pinter is available on Amazon.

He can be contacted at [email protected]

His website is www.WorkingWithPinter.com