To speak about Commedia dell’Arte is – essentially – to enter a very complex and heterogeneous field of theatre and live performance: it is to step into a story that lasted from the end of the 16th century until the beginning of the 20th century – in southern Italy, for example. This complexity arises because of the conflict between the true development of a living cultural phenomenon and the need of Theatre History researchers to create a category that collects similar experiences occurring in the same historical period or in the same country or continent. That’s why, in a meeting between Carmelo Bene and Dario Fo, when asked about Commedia dell’Arte, Carmelo Bene said, “it never existed.”

But what is Commedia dell’Arte? Such an hard question, but we can start by explaining what the definition “Commedia dell’Arte” means.

What is Commedia Dell’Arte?

The term “Arte” in Commedia dell’Arte, for example, does not simply stand for the word “art” as we use it today: in medieval times, cooperatives of “Jobs and Arts” were established, under whose protection every kind of artisan and craftsman could be found.

Therefore,

This definition became necessary when travelling companies of comedians started having problems as they found theatres in Italy were being used by groups of amateurs, whom they started calling “job thieves.” In order to publicly separate their work from the amateurs, they started calling their theatre “Commedia dell’Arte.”

The origins: Travelling Company of Comedians

As you can read above, I have already given you a kind of element about what Commedia dell’Arte is when I wrote “travelling company of comedians”: this is something closely related to many of the characteristics of the Commedia dell’Arte genre. In fact, when we speak about Commedia dell’Arte, we are speaking of a theatre genre that was born in Italy at the end of the 16th century and was performed by families of great Italian actors, such as the Andreinis, the Biancolellis, the Gelosís, Silvio Fiorillo, Tiberio Fiorilli, and many others. It is important to understand that entire families performed it, and it was inherited through generations in terms of repertoire, masks, roles, and scenarios, because this is very strongly linked to the way it was performed.

We must understand that these travelling groups and their way of living created a perfect fusion between their theatre and their life, which is the opposite of what we today call professionalism or “being an artist.” Also, these life conditions are very different from the “glamorous” idea we have of actors, artists, performers, and entertainers today. The Comedians dell’Arte are similar, from our point of view, to beggars, and in fact, it was not an honourable condition to be a Comedian at that time. Still, from what we know, we are speaking of some of the most talented and ingenious actors of all time, able to dance, sing, play instruments (mostly the guitar), juggle, walk on the rope, and perform all the acrobatic acts we now see in a circus. They also created their masks and original characters, which are still alive in our comedies and movies today and which influenced and gave birth to European Modern Theatre. Furthermore, they created new stories and performances every evening through improvisation on simple plots called “Canovaccio.”

It introduced some of the most well-known peculiarities of Commedia dell’Arte: masks and improvisation.

What is the Canovaccio?

Canovaccio, the Skeleton of the Plot

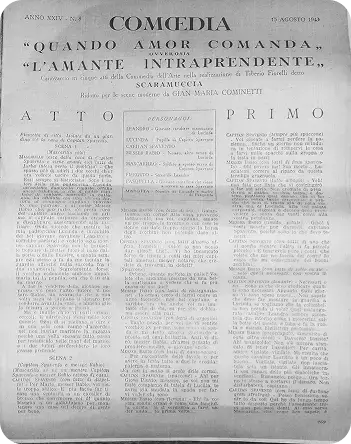

The “Canovaccio” can be described as an ancestor of what we call today a script: a Canovaccio is like the skeleton of the plot, of the story we are playing on stage.

On it, we can find the scenes, some main lines, the entrances and exits of the characters, and the arguments they must discuss to move the story forward. There are also some verses for the ending, at least.

Improvisation in Commedia dell’Arte

That was all: the actors created the entire development of the performance—every event and gag—live on stage. But when we talk about improvisation, we are not referring to something like what we recognise as improv theatre, or exercises in improvisation that stimulate the creativity of young actors. Nor is it something that happens purely by instinct.

The script is in the mask: if an actor knows his mask well, he will never make a mistake in his choices, and he will find that the mask guides him even more than a written script would. He has no choice but to play the mask as it demands to be played.

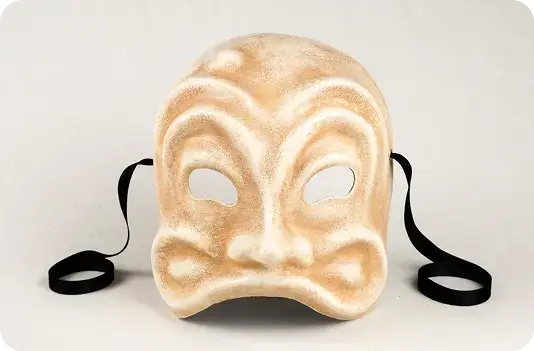

Masks in Commedia dell’Arte

Since Commedia dell’Arte is a genre with very ancient origins and roots, we must understand that its masks are strongly related to—or rather, an evolution, transformation, or adaptation of—the masks of Roman comedy, called “Atellana” (named after the city of Atella in Campania, southern Italy), whose greatest authors include Plautus and Terence.

In this ancient comedy, we find four different masks, which are considered the foundation of all those in Commedia dell’Arte:

• Pappus – the greedy master

• Maccus – the clever servant

• Dossenus – the evil, deformed servant

• Kikirrus – the only non-anthropomorphic mask, representing an animal: a rooster

To these four masks, we can add the “Miles Gloriosus”, the arrogant soldier who is the protagonist of one of Plautus’ most famous comedies, and “the Lovers”, a much later mask that was already performed without a physical mask—a sign that this tradition was beginning to fade.

1. The Masters masks

Associated with farm animals such as pigs, cows, and horses, as well as crows and parrots, this category represents the bourgeoisie, which was emerging at the time. Merchants, doctors, lawyers, and landlords, despite not being born into noble families, were becoming powerful and rich through their possessions, greed, opportunism, or hypocrisy. They descend from the mask of Pappus and survive in characters such as Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Two examples of the most famous masks of this category are:

Pantalone mask

Between a crow and a giant parrot

Venetian

Merchant

The Venetian mask of the greedy old merchant, Pantalone, is dressed in red and black, with clothing that appears poor, old, and in bad condition.

His archetype animal, somewhere between a crow and a giant parrot, strongly influences both his voice and body movements. His internal conflict lies between his obsessive desire to keep his money safe—similar to Euclione in Plautos’ Aulularia, who guards his pot of gold—and the deep distrust he feels toward those around him. He is powerful, yet weak.

He is constantly surrounded by his servants, primarily Arlecchino and Colombina. Since he often wishes to marry Colombina—another aspect of his character is his delusion that he can choose a young wife and act as though he is youthful, healthy, and vigorous, which he clearly is not—he finds himself in conflict with Arlecchino, Colombina’s lover and sometimes husband.

Dottor Balanzone mask

The pig

Bologna, in Northern Italy

Scientist

Dottor Balanzone is a mask from Bologna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. His archetype animal is the pig, evident in his laugh, which resembles a pig’s sound, and his body, which appears large and wealthy—symbolising someone who eats abundantly, a sign of good social status. He is a scientist, and his mask, shaped like a pair of glasses with a black nose, reflects his scholarly nature.

His costume is mostly black, with white socks, and he often wears the typical tocco hat, traditionally associated with those who have earned a diploma or doctorate. His speech is filled with Latin words, which he uses to flaunt his superior education and culture. However, his excessive verbosity often leads him into endless, nonsensical explanations of simple phenomena, ultimately making him an obstacle to any action needed to resolve the situation or problem faced by the characters on stage.

His costume is mostly black, with white socks and he often wears the typical “tocco” hat of someone who took a diploma, or a doctorate. His eloquence is full of latin words whit which he loves to show off his superior education and culture, but often brings him into infinite nonsense explaining of very simple phenomenon, ending in being an obstacle for every action must be done to solve the situation, or the problem the characters are facing on stage.

2. The Servants masks

This category includes a subcategory: the Zanni, a mask that is less defined than the specific characters of this group, such as Arlecchino or Pierrot. The word Zanni comes from the Venetian dialect, which is known for transforming the “G” sound into “Z”—originating from the name Gianni, a short form of Giovanni, which, in the countryside of the Veneto region (between Bergamo and Padua), was pronounced as Zanni.

This is the ancestor mask, derived from Maccus, which encapsulates all the characteristics of the servant figures: their trickster and clever nature (as seen in Brighella or Truffaldino) or their naïve and foolish side (as in Pulcinella and Arlecchino). The category of animals that inspires these masks consists of courtyard animals—cats, birds, roosters, and chickens—except for dogs (you will soon learn why).

Arlecchino mask

Cat and monkey

Bergamo

Servant or Zanni

One of the most famous masks in the world, it comes from Bergamo and takes its shape and movement from two animals: a cat—which also resounds in his voice—and a monkey. This may seem strange if we consider the definition of courtyard animals, but it makes sense when we remember that Venice was a city of travellers and merchants—an important centre where every kind of extravagance was possible, and all sorts of exotic goods could be found, including monkeys brought by ships returning from distant lands.

His name comes from the German “Herr König”—the King of Hell. This gives us information about the origins of the mask—origins that still survive in its shape. We can see a red mark on Arlecchino’s forehead: this is what we call a broken horn, and it is proof that, at the beginning of his journey, this mask was originally a demon. In fact, in the countryside of Bergamo, during ancestral pagan rituals, it was common to see the figure of the “King of Hell,” who was responsible for bringing the souls of dead children into the Otherworld—a role similar to that of Charon. Over time, however, this dark origin evolved, transforming into the childish, burlesque servant we all know today. His costume also changed—from a large white dress, making him look like a ghost or a cloud, to his multicoloured suit, made up of various patches of fabric his mother collected, as their poverty did not allow them to buy him a new outfit.

Arlecchino is always in love with Colombina. His walk resembles that of a monkey, while his leaps recall a cat’s movements. He combines his immaturity and naïve nature with laziness, an enormous hunger, and a love for life’s simple pleasures.

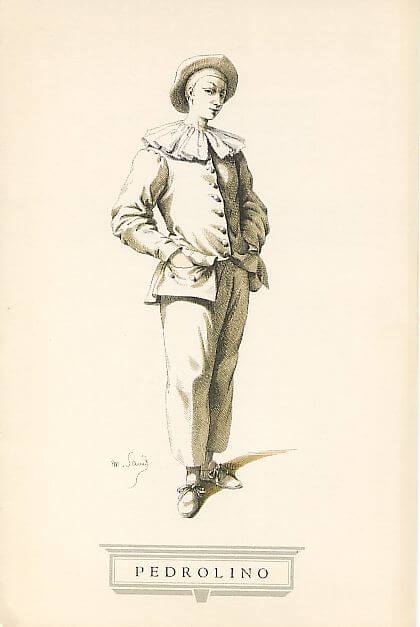

Pierrot (Pedrolino) mask

Originally associated with birds (such as a chicken or pigeon), reflecting his early roots as a Zanni.

Lombardy

Servant (Zanni)

Becoming famous in France as a romantic character, especially in the 19th century, thanks to the French mime Jean-Gaspard Deburau, this mask was originally Italian, known by the name Pedrolino. It was a unique mask, as it was the only servant’s mask to have such a strongly romantic characteristic—being in love with the Moon, always seeking love more than food, wine, and women.

This may also explain why it eventually disappeared—this deeper, more sentimental nature was unexpected for a servant’s mask, and audiences likely began to find him less amusing than the other characters.

3. The Captains masks

We can easily present Commedia dell’Arte as the theatrical representation of the struggle between these two classes:

• The servants, who are less powerful but more clever than the masters.

• The masters, who are in power but are tricked by their servants.

Between these two categories, we find the category of the Captains, which has, as its archetype animal, dogs and hounds. This gives their masks’ noses a long shape and characterises their loud barking voice, as well as their way of being both arrogant and cowardly at the same time.

They are also a parody of the foreign domination that appeared in Italy and France, as Commedia dell’Arte and its travelling groups, along with some of its best actors (such as Domenico “Dominique” Biancolelli and Tiberio Fiorilli), became very famous in France. Matamoros, the mask of the Spanish soldier fighting against the Arabs (Moros), and Scaramouche, the mask invented by Tiberio Fiorilli, are prime examples. Fiorilli became the favourite actor of King Louis XIV, the first comedian of the kingdom, and the mentor of a very young Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, later known as Molière.

The influence of Commedia dell’Arte in modern theatre

From this event we can understand the great influence Commedia dell’Arte had on the development of the European Modern Theatre: sometimes also being above its time.

💡 Fun fact: While in the Elizabethan Theatre, in Shakespeare, women weren’t allowed to perform, in Commedia dell’Arte we have the examples of Isabella Andreini and Caterina Biancolelli, who were not only important and esteemed performers, but also playwright and poets.

Commedia Dell'Arte Influences on Shakespeare

But we can also have an idea of how popular and fascinating Commedia dell’Arte was for artists like Shakespeare, by noticing how often he, using a meta-theatrical technique, represents the arrival of travelling group of actors such as the ones in Hamlet, or the Botton’s lovely but totally messed up company, involved in the preparation of a tragedy for Theseus’ wedding celebrations, in “Midsummer night dream”.

Also we can notice he quotes the word “zany” in the second scene, act V, of “Love Labours Lost” (“some carry-tale, some please man, some slight zany”), proving he knew and he met the mask and the character of the Zanni.

Also the way he contaminates his finest poetry with some of the most vulgar jokes or word-tricks, makes us suspect he met this kind of very primitive street theatre.

Goldoni and Molière and the Birth of Bourgeois Comedy

It is even more evident if we look at two of the main authors of the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe: speaking of Goldoni and Molière and the birth of bourgeois comedy, of the pochade and vaudeville as they existed and evolved in Europe since the beginning of the 20th century, we can easily connect it with the background structure and tradition of Commedia dell’Arte and its masks and canovaccios

As for Molière, having as his mentor one of the best comedians of all time, it is clear to suppose how much he was influenced in writing his comedy. Characters like Arpagone and Argante are clear descendants of the mask of Pantalone. The same goes for characters like Marietta/Colombina, Angelica, Scapino, or the characters of the lovers.

The same is true for Goldoni, who, in the first part of his playwriting career, used the masks ( Truffaldino, the servant in The Servant of Two Masters) and adapted the classic dynamics of Commedia dell’Arte’s plots to a more complex narrative arc, with deeper and more layered stories. He then slowly tried to emancipate his theatre from that tradition by abandoning the masks, writing new comedies, and enacting his “Reform” to create a new theatre that could please a new, more powerful and educated audience seeking a more sophisticated form of theatre.

Finding the “Truth” Behind the Mask

Anyway, also if our taste in theatre and acting style after Stanislavski and Strasberg is focused on a deep psychological analysis of the characters and on the research of an inner truth, of a Hyper-realistic and naturalistic approach to the acting performance, still the telluric power of the masks is somehow resisting for many reason: one of the psychological effects that the mask gives to the actor and to the audience, is the concrete idea of not being ourselves anymore, not recognizing our voice, our face; our body being involved into an uncomfortable work to overcome the expressive limits the masks imposes to our facial mimic.

Also, since the mask, as well as a surrealistic painting, recalls something of unconscious, primitive, animalistic and immediately excludes every possible concept of “truth” and “naturalism” – as well noticed by Wilde and Pirandello.

The mask shows, with its vanity, the vanity of everything and by declaring its lie from the beginning, it is able to reach another kind of deep artistic sincerity, which is impossible to find in any human face. Forcing the actor to play with all his body and energy, transforming his voice, his breath, his appearance, the mask is able to recreate a sacred, ritual dimension on stage, as in the origins of our theatre and of every form of art.